insert a shunt into the ventricle to drainĬerebrospinal fluid (to treat hydrocephalus).

Burr holes and keyholes are used for minimally invasive procedures to: Stereotactic frames, image-guided computer systems, or endoscopes may be used to precisely place instruments through these small holes. Small dime-sized craniotomies are called burr holes "keyhole" craniotomies are quarter-sized or larger. Some common craniotomies include frontotemporal,Ĭraniotomies vary in size and complexity. “We have the ability to use the operating room not only as a place of healing,” he says, “but also as a place where we can push the boundaries of how we can operate in the future.Craniotomies are often named for the bone being “Then we had to get back to work closing up his skull.” While the operation was the first of its kind, Pilcher sees it as only the beginning of what could be accomplished in translating research into practice and back again. “We all applauded, of course,” Pilcher says. The moment of truth came when they gave Fabbio his saxophone to play a song, which he performed perfectly. In the operating room, Fabbio repeated the exercises while Pilcher punctured the tumor like a balloon and gingerly peeled it off the brain.

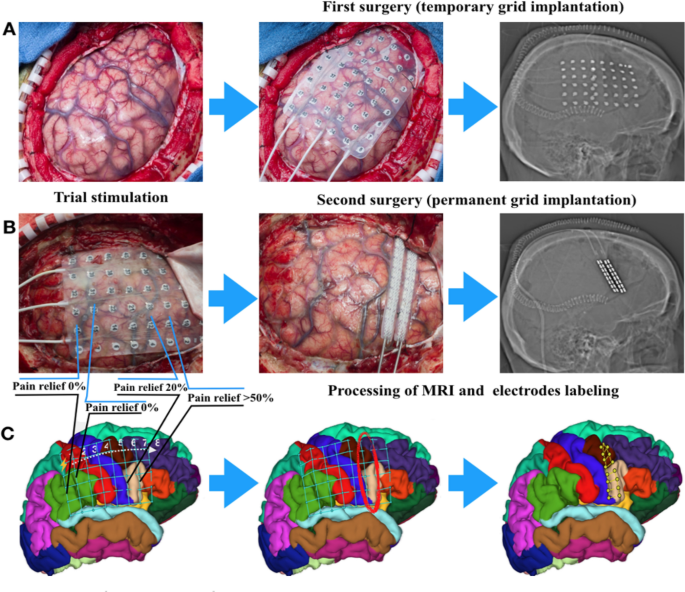

#BRAIN MAPPING PROCEDURE SERIES#

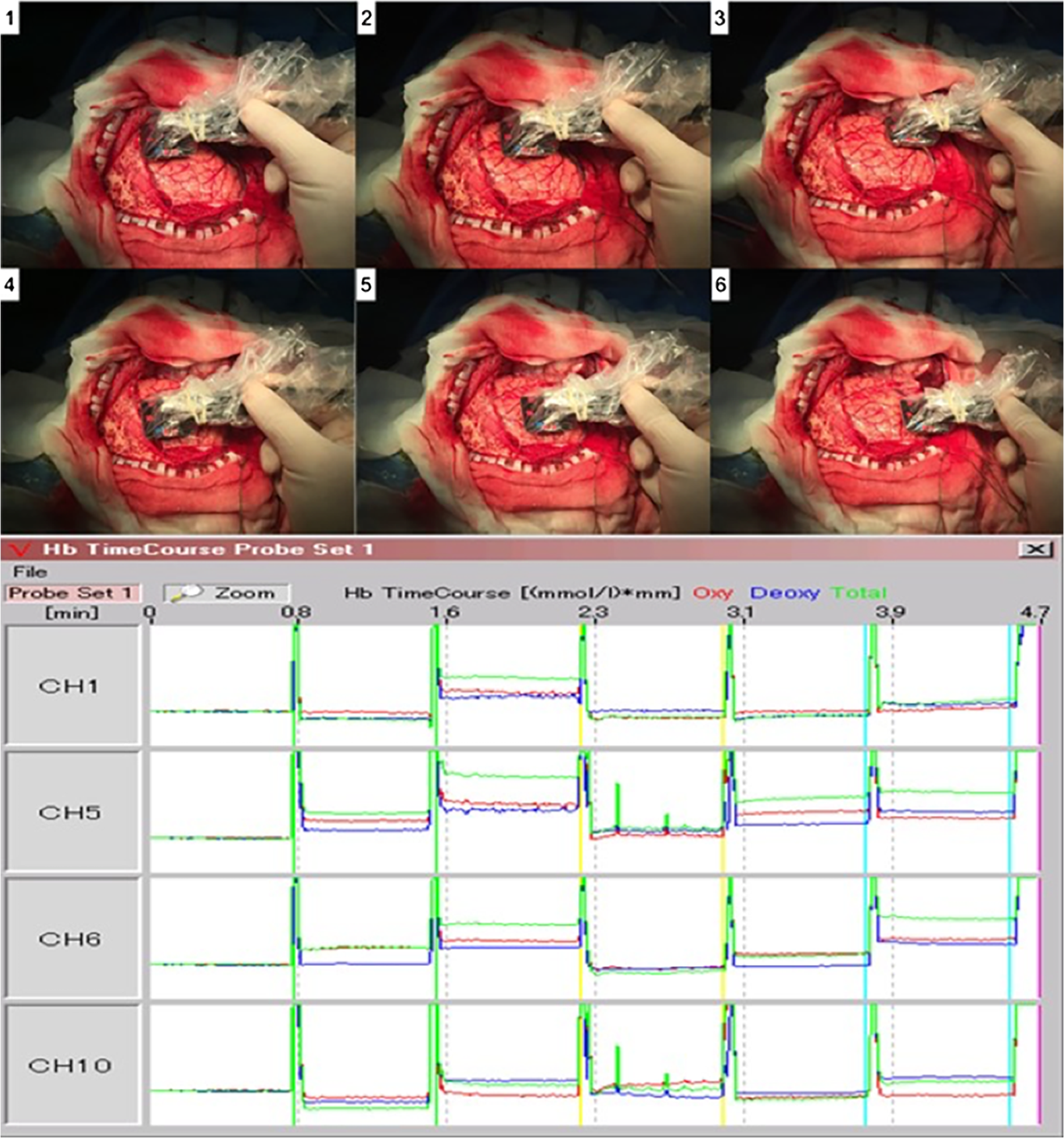

A doctor in Utica discovered the brain tumor and referred him to Pilcher, who worked with Mahon and a music professor to devise a series of musical exercises that would help create a three-dimensional map of the brain identifying what parts Fabbio used while he played. Last year, however, those harmonies stopped, and music seemed flat and one-dimensional. In the case of Fabbio, he had a gift for music - hearing harmonies even in mundane sounds like his electric toothbrush. “I tell patients with brain tumors, ‘We need you to leave the operating room the same person you came in as,’” Pilcher says. Working with Mahon, Pilcher has patients come in and spend several days performing tests to map their brains to identify areas essential to different tasks. So while scientists have been able to identify general areas that correspond to functions such as speech and motor control, they can’t pinpoint the exact spots in each person. Just as people vary in height and eye color, so, too, do our brains differ. Now chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Rochester Medical Center, Pilcher initially began performing awake brain surgery on epileptic patients in the ’90s, before initiating the brain mapping program in 2011 with Brad Mahon, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences. At the same time, he fell in love with central New York, eventually moving with his wife, Allyson, to pursue an MD and PhD in neuroscience at the University of Rochester. “I became extremely interested in why people behave the way they do,” he says. Pilcher developed a fascination for human behavior as a sociology and anthropology major at Colgate. This summer, Pilcher became the first neurosurgeon to use brain mapping for the part of the brain that controls music - cutting a tumor off patient Dan Fabbio’s brain while he sang in the operating room. During surgery to remove a brain tumor, for example, Pilcher asks his patients to perform tasks involving language or motor skills, then watches the parts that light up on the fMRI screen, so he knows where to avoid cutting with his scalpel. “Unless they can contribute, we can’t do the surgery.”īrain mapping is at the cutting edge of neurosurgery, wedding research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with clinical practice. “We tell them at the outset that they have a very important role to perform,” Pilcher says. As a practitioner of awake brain surgery, Pilcher needs his patients to be conscious while he works so they can help him in an extraordinary task: mapping their own brains. Then, he asks his patient how he or she is doing. When Webster Pilcher ’72 performs brain surgery, he first drills holes in the patient’s skull, removing a portion of the bone, like taking the top off of a Halloween pumpkin.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)